Although fire lookouts continue to be critical front-line components of our forest system’s battle to detect and prevent wildfires, their roles often times go unnoticed, due largely to both the manual nature of the work involved and the quiet, extremely solitary nature of the working environment. Leif Haugen is a fire lookout in a remote corner of the Flathead National Forest in northwestern Montana, and each summer he lives and works alone on top of a mountain three miles from the Canadian border. A simple, somewhat primitive one-room structure serves as both his home and office; however, what it may lack in amenities (neither electricity nor running water are available) is more than compensated for by the majestic, 360-degree views of the world that his perch provides. With only a remote radio to keep him connected to the outside world, Leif’s primary responsibility is to scan the valley floor for any signs of destructive fire activity – one which calls for enduring long stretches of tedium and an eagle’s eye and quick response the moment fire is spotted or lighting strikes in the distance. There are approximately 500 active lookouts currently operating in some of the most rugged and desolate outposts of the American West. The Lookout captures both the critical nature of one fire lookout’s work as well as the life of quiet, contemplative solitude which accompanies his job.

Month: September 2014

Charalambides – Dormant Love

From A Vintage Burden, 2006

Richard Skelton – Landings

I’ve come back to this a few times recently, for various reasons. I have a suite of reservations now, but this is more due to what came post-Skelton – the channel he opened and what subsequently came through. In many ways he’s a direct analogue for Robert Macfarlane; and there’s a certain sense of mirroring between what happened in nature writing post The Wild Places and what came after Landings – the first time Skelton was genuinely uncovered. I suspect it’s the sheer weight – the avalanche – of similar work that followed, the shy coppice-clusters of earnest aesthetes suddenly given the confidence to share their inner geographies, their open-pored sensitivity to the pull of the land. But whatever the reasons for the about turn, it does pay to return to the source every so often; if only to be reminded that you were right the first time and that these things, however buried, still have the power to knock the breath out of you. This was first published in early 2010.

Thing-poems of the moor…

Landings was Richard Skelton’s second release for Type, after 2009’s Marking Time. He had behind him an array of releases, put out under various pseudonyms: Clouwbeck, A Broken Consort, Carousell, Riftmusic. All of these releases had been on small labels, or on Skelton’s own Sustain/Release imprint, and were invariably in tiny print runs. They were all constructed from comparatively little, and incredibly hard to describe – field recordings, a bowed string, a violin scrape, the arched wheeze of a concertina – yet they felt at times as grand as someone capturing the sweep of time, and the tiny movements of vibrating molecules. All of Skelton’s releases worry at similar themes: how we reconcile our self to place; how we track our passing through intimate and strange landscapes; how we cope with the climactic intrusions of grief. Landings followed these themes and with the accompanying text drew everything into sharp focus. It was the culmination of years of the near-obsessive recording of Skelton’s collaboratory relationship with the West Pennine Moors around Anglezarke. It is a conjuring, a chronicle of a disappearance, an insight into the process of healing. It felt like something of a summation. It is still extraordinary.

All of Skelton’s work to date has been an explicit response to the death of his then wife Louise in 2004. His body of work – both the recorded medium and the exquisite packaging each release comes in – is a memorial to her passing and an act of remembrance. Landings, and the text that accompanies it (which appeared online as an ongoing diary between 2005-2008) is direct and nakedly open response to this event. In his relationship to the moors around Anglezarke, he has forged a collusion with the land that has allowed him to explore the inner landscape of his own grief. There is a kind of projection at work here, an outward mapping of the traumatic space, in which Skelton has sought to lose himself completely. Instead over time- and without wishing to presume too much – what seems to have occurred in this collaboration with the brows and slacks of the land, is both an intimate knowledge of place, and an intimate knowledge of self. The sparse text of Landings, and the exquisite, gripping nature of the recorded music is our privileged glimpse into this sacred process.

Skelton’s method in exploring and cataloguing his experiences of the landscape around Anglezarke was to attempt to become a kind of conduit – both for his own responses, and in the more complicated space of interaction between place and self. Initially, he would make field recordings of the ambient sounds – the whine of wind through a ruined farm, the grakking calls of rooks – and then augment these with his own instrumentation. This gave way to him actually making recordings in situ, using the moors as an open-air studio. Occasionally he would leave a dicatophone in the trees, returning the recordings to their original source – what he called ‘returning the music back to its birthing chambers’; or he would secrete a diary beneath stones – a votive offering. Over time though, he realised his methods were obscuring and obstructive, as if this method of recording the intimacies were somehow mediating his ‘true’ experience of the landscape. Instead, Skelton trusted to his imaginative recall, and instead used elements of the landscape to aid this collusion at one remove: a bone plectrum, the scrape of tree litter on metal strings.

This gradual exploration and layering of experience, both sonic and actual, is a fundamental aspect of the music on Landings. It is mirrored in the accreted layers of sound, which at times become almost textural, tactile. On a track like ‘Thread Across the River’ (where Skelton comes closest to sounding remotely like anyone else, in this case Set Fire to Flames, another project that was set up as a collaboration with place, this time a derelict mansion in Montreal – though there is something of Eno in ‘Green Withins Brook’s broad chords, and if Landings has an antecedent, then Eno’s Ambient 4: On Land is probably it) there is a simple layering of bowed cello and violin but they are treated in such a way as to sound like natural phenomena. This effect is added to by the way the track gives out to the thin cries of meadow pipits and the haunted, bubbling uprush of curlew calls. The closing track, ‘The Shape Leaves’ – which refers back to a CDR release from 2005 – comes as if from behind a curtain of moorfog, a distant piano figure beneath bowed strings, eventually giving out to an eddying storm of cymbals before returning to the murk. In truth, individual examples are largely useless, as the whole record is so of its own sound world, and so wound into the whole act of its creation, that these qualities are suffused and implicit. If you were to try to figuratively pull up one corner of it, you’d find the rest attached.

With Landings, Richard Skelton has created something vast, resonant and timeless. The work and drive behind it has created a document that requires a new kind of categorisation. It has gravity in the very real sense of that word; indeed, at times it seems to possess its own geography. It is a Romantic document, a record of an intimate relationship with place and a minutely observed mapping of the local – it might come to be put alongside Richard Long, Gilbert White, Alice Oswald, Ted Hughes. It’s also an almost unbearably moving chronicle of a grief observed. Sometimes you just have to stand back and admit a certain privilege at coming into contact with something. This is one of those times.

Stewart Lee and the Pueblo Clowns

In 2006 Stewart Lee travelled to Taos in New Mexico to see the Pueblo Clowns and make this two part documentary for Radio 4. The clowns, unlike the cartoonish, vaguely melancholy characters that occupy the edges of our own culture, are – literally – unrepresentable, figures who operate in some shadowy shamanic space between worlds and who still wield a terrifying raw power that approaches the sacred.

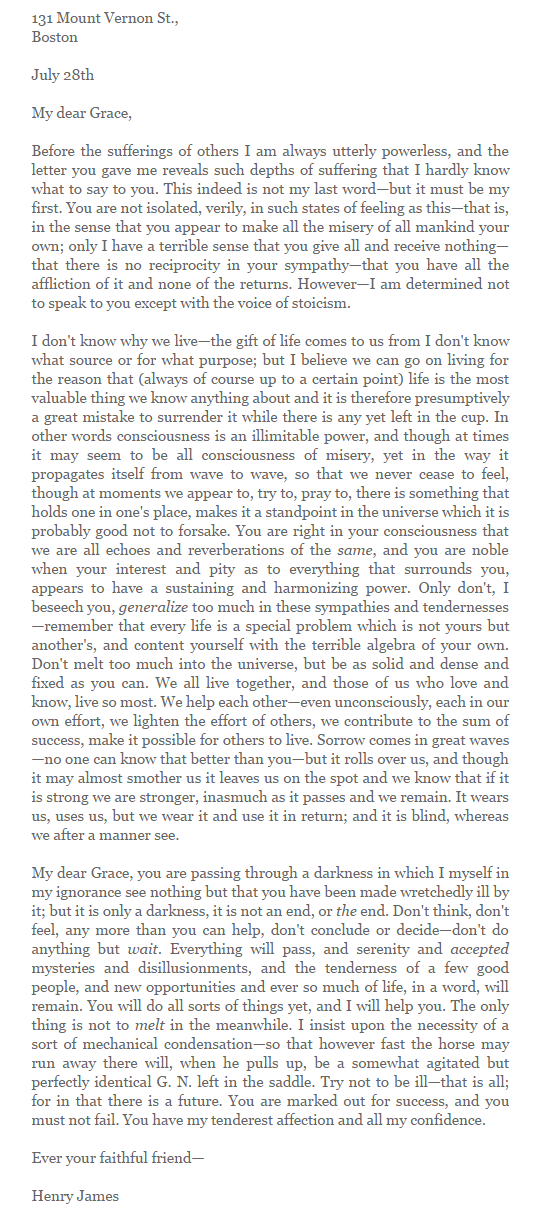

Not to melt in the meanwhile

Henry James in 1883, writing to a friend who was suffering with depression after a recent death in the family. Staggering. From the very excellent Letters of Note.