This was first posted on the Liminal back in late 2012. Rob’s done a ton of things in the interim, all worthy of your eyes and ears. You can read about them here, and follow him on Twitter.

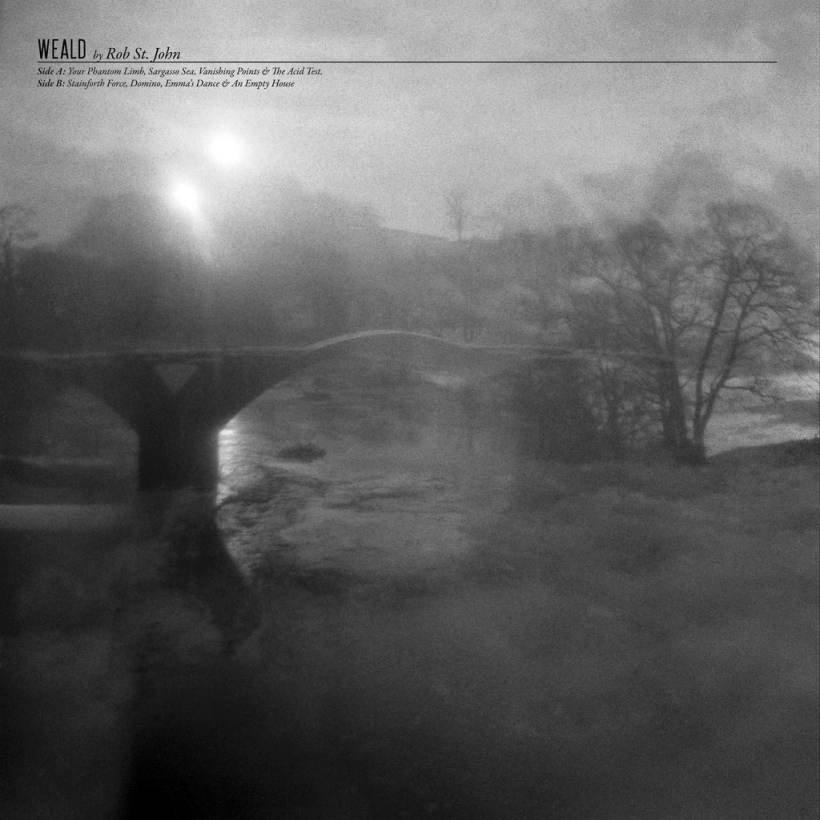

Rob St John feels like an avatar of an older tradition. The ‘folk’ tag has become somewhat hollowed out, a dead signifier; but vestiges of the tradition remain, and remain oddly powerful in their ability to both evoke the particulars of place and lever open channels to the past. St John, across a variety of projects – musical and otherwise – has revealed a keen eye for specificity and an alchemical descriptive capability; he also appears to be adept in listening to the clamour and babble erupting from that open channel and focusing it into some semblance of a coherent narrative. Weald, which came out late last year on Song, by Toad, was a record of what you might call, in a non pejorative sense, ‘hollowed-out’ folk music – the tracks were as much resonating caverns as actual songs. But there was also a smeary, vague quality to it: on a molecular level syllables colaseced, meanings blurred; on a broader sonic level, instruments followed this pattern and cross-fertilised. The result was an enigmatic thing, a gothic puzzle to which the ear slowly attuned. St John has been busy since, curating here and travelling there. We talked about Weald and the various projects St John is involved with – now and in the coming months.

Where are you know – what’s happening? And where have you been in the last month or so?

I’m currently in Lancashire, where I grew up, watching the rain fall outside. I’ve been travelling around the Western and Northern Isles of Scotland with my partner, for the last few months: walking, writing, fishing, attempting to keep reluctant peat fires going.

You recently wrote a soundtrack for the Jeremy Deller’s documentary about Bruce Lacey – could you tell us a bit about how you became involved and how you came up with a soundtrack?

Jeremy Deller and Nick Abrahams got in touch to say that they’d heard my record and whether I could contribute some new music to the ‘Bruce Lacey Experience’ documentary they were putting together: specifically something to soundtrack Lacey’s free festival days. I’d been planning to move away a little from the dense, droney and dark thing we did with the last record. Whilst it was probably appropriate and cathartic at the time, it’s not a reflection of where I am now – both personally and musically. So the recording was an opportunity to tie together some of the music that has been recently exciting me lately and experiment with some new sounds. It was good to play some soft, rolling folk guitar again, underpinned by whirring synth and flitting flute, fiddle and saw, all recorded live. We recorded about 15 minutes of new music. The film showed at Camden Arts Centre until September (2012) and will be released on DVD through the BFI later in the year, I think. It’s fantastic to be involved with a project related to Lacey, he’s a national treasure, an eccentric mischief (and myth) maker. Maybe we’ll sort something out with the rest of the recordings for a small release, but it’s likely that the ideas and textures will turn up on the next record.

This is probably a bit of a loaded question, but would you categorise Lacey’s stuff as whimisical? What do you make of whimsy? And the notion of Lacey as some kind of shamanic figure?

In some ways, I suppose, but then again whimsy is a very subjective idea, isn’t it? In the documentary, he describes himself as a ‘professional piss taker’, I think. There’s a tradition there in parallel to the Goon Show and similar – seemingly light, silly entertainment that serves to skewer and satirise its subjects on a very subtle level. I’m a fan of his later works: as you say his shamanic, free festival Earth Rituals in the 70s, and his proto-play work, installing great climbing frames for inner-city kids. There’s a curiosity and wonder that runs through his work, a freewheeling optimism, confidence and willingness to experiment and invent. I think the idea of curiosity and ‘I wonder’ underpins many important discoveries – whether in the arts or sciences – but is something that is being increasingly lost by many people creating ever smaller frames of reference through the way they interact with and curate the technology around them, a safety net that it’s scary to move beyond.

To come back to whimsy, I guess I’ve no radical opinion. I suppose Weald was the opposite of a whimsical album, wasn’t it? It was very dense and layered, and I wanted it to reward repeated listenings, to retain an element of obscurity to allow the listener to attach their own thoughts, experiences, whatever, to. But as I say, whimsy can be a vehicle through which to approach and express darker, more complicated subjects sometimes. Look at the Syd Barrett solo albums: he was clearly suffering with mental health problems, and the records are laden with whimsy, with terrapins, octopuses and effervescing elephants. There’s an immediate surface of whimsy over a darker undercurrent.

You said that you’re looking to move away from the density of Weald – what’s driven that? Did I read somewhere that you used 80-odd tracks on there?

I think you need to keep evolving – however incrementally – in terms of the music you make. It’s so easy to be pigeonholed, and I respect artists who can continually reinvent themselves. Weald was the first of (hopefully) a set of records I’d like to make, and whilst the weight of it (lyrically, thematically, musically) suited my state of mind at the time, it isn’t a record I want to make again. It was cathartic, something between miserable and whistleable, but you need to keep moving.

We used 80 odd tracks – yes – but across 8 songs that isn’t really a great deal. Weald was a very quickly recorded thing – we spent two days on it from start to finish – with a few mixes and that was it. Layers upon layers, conducting players coming in and out to play their parts. We’ve played these songs live for a year or so as a relatively settled band and they’ve certainly evolved. I think it’s this evolution – for the better – that makes me want the next record to be more band-led. We’re mooting putting it out as a ‘band’ record under a different name, which would be exciting.

I’ve all but written the next record, mostly during an intensive few days in a house that once belonged to Hugh MacDiarmid on Whalsay off Shetland, trying (in vain) to keep a reluctant peat fire alight. Perhaps, not surprisingly, after reading On A Raised Beach for the first time whilst I was there, I became a bit obsessed with deep time. It’s very acoustic guitar led – more in common with ‘Emma’s Dance’ off the last record than anything else – and very lyrically dense again (positive, this time!). How to write about positivity and happiness without lapsing into cliche and hyperbole is a new challenge.

You’re quite protective, if that’s the right word, of the meaning of your songs, or at least reluctant to say what they’re ‘about’ as such. I was quite intrigued by the ‘I never came down from that trip’ line in ‘The Whites of Our Eyes’ – is there anything obviously psychedelic in what you’re doing

I sing ‘I never came down from that tree’….but a fair few people have heard ‘trip’…so when we play live I’ll intersperse the two words to blur things a little. I like mishearings such as this – attaching your own meaning, mythology, or whatever. ‘Whites of our Eyes’ will be on the next record, so I guess I’ll have to solidify things a little on it – at the moment it blurs into ‘Domino’ during the live show in a 15 minute squall of feedback and drone (maybe the next record won’t be quite so quiet…).

That’s another thing that’s interesting, whether the recording is the definitive version of a song, or just a snapshot in a continuum (albeit one that’s more mapped out and planned than others)? I’d say every song should continually be in flux, every set should bring in something new or otherwise forgotten, to keep it fresh, both for us and the crowd. At gigs, we play as a band, and try and make each show a one-off, responding to the surroundings, the crowd, the other bands on the bill. Pushing and pulling songs into each other, expanding and contracting them. As a result, we’re playing far fewer shows than perhaps a year ago. In the summer before Weald was released, I played a lot of shows solo in small black-box venues in small towns to small crowds. I’d rather we played as a band, in interesting venues, where we can tailor the set to suit. I’d like to start using projections more during shows too.

To go back to meaning in songs, they’re intentionally left relatively ambiguous. I’m interested in dense, cryptic lyrics that draw on a whole range of ephemera and situations, from daft (whimsical?) to serious. Every line of every song should mean something to you, but also provide a host of scattered satellites for the listener to anchor themselves around, whether that’s through mishearings or whatever. I like collecting words: I fill notebooks with them, and then have to drastically cull them from new songs, save having to provide a thesaurus in the liner notes. It’s about finding the line between the real and the imagined, quiet revelations that most of us experience in one way or another. Everything that goes into the songs is real and thought through, but I’m interested in how they are interpreted so differently.

I’m intrigued by your use of obscure words and dialect-specific terms and phrases – particularly Lancastrian and Scots. Gerard Manley Hopkins used to go out ‘collecting’ words – from specialist dictionaries and dialect dictionaries etc. He had a collection which he called his word hoard which sounds kind of similar to your approach. Is there a certain kind of magic in these old, dying words?

There’s a magic in the unusual and useful, I think, in the place and time-specific, the words that pop up out of a locally specific need, rather than necessarily their scarcity or danger of extinction. Maybe it’s important not to become some lyrical magpie, picking and choosing indiscriminately, but I think you can use certain words and phrases to ground your songs in specific places, times, atmospheres, and give the listener another chance to follow up on things. I enjoy art, records, books where you feel compelled to pick up a notebook and scribble down references, things to follow up, ideas. I don’t know a great deal about Hopkins, except a little about his proto-free verse – sprung rhythm – and the way he moulded and melded words together. I like the way Nabokov does a similar thing, his use of portmanteaus, moulding words to new uses, a playfulness in his structures, rhymes and narrative riddles.

We have a funny tradition of dialect poetry and song in Lancashire. It’s still strong as a culture, but I think that the emphasis on dialect and the use of anachronisms can sometimes come at the expense of content, maybe performers set themselves up as some sort of novelty act rather than as a documenter of what’s actually going on. So you have to be careful, y’know? For me, folk music (if you even need to define it), is all about people writing eloquently and interestingly about their condition in a certain place.

Domino’ is probably the darkest and densest thing on Weald – it’s got that Old Testament fire about it. I’ve puzzled over the title and the lyrics and only found out recently that the word comes from the French for mask. How did the track come about?

‘Domino’ is the oldest song I still play. It began as open-tuned folk song, and it’s about self-preservation and kindness. Whether they’re mutually exclusive. Maybe it’s also a little about sea trout fishing. It’s now a real cathartic squall of sound when we play live, like we egg each other on to make it louder than the last. I like that association with ‘mask’, it’s quite fitting, I guess.

Are you wary of the ‘folk’ tag? Is it still useful as a description?

I’m not wary as such. Folk music is still such an important, meaningful thing, but its very nature means that it is (and has been) open to the push and pull of change and appropriation. And that’s largely good, I think, but it means that ‘folk’ means multiple things to different people, is open to flux and change, and probably always will be. Look at the British Folk Revival in the 1950s and 60s. We often look back to that era as part of an unbroken tradition, but in reality there were a whole bunch of agendas playing out with Ewan MacColl and others over what folk was, and for whom. Similarly, go back to the start of the 20th century, and to the work of folk song collectors such as Cecil Sharp, again the notion of ‘folk music’ was wracked with questions of authenticity and appropriation.

Regardless of any of this, people singing out together with whatever instruments are to hand will never go away. Like I said before, I think more than instrumentation or sound, folk music is about telling stories and histories of place, landscape and local distinctiveness. So, I guess we do a lot of things with our music that have a lot in common with traditional folk. We use a lot of close, but often improvised, vocal harmonies, and we’re increasingly using fiddles, recorders, autoharps, picking out drones and modal scales. It helps that Tom Western (who plays keys) is a researcher into Alan Lomax and the practice of field recording. The next single we’ll put out is a Lancastrian traditional song called ‘The Charcoal Black and the Bonny Grey’, a split with Woodpigeon, both of us tracing our family histories through folk songs.

You’ve worked in a number of ‘collective’ situations – in and around Edinburgh, mostly. Has that had an effect on your writing and the style of music you play? Is there more forthcoming from the Braindead Collective and Eagleowl?

Yes, I’ve played with a lot of people over the last few years. I play full-time in Eagleowl and Meursault, and I help out other projects from time to time. Things were especially fertile around 2007-08 in Edinburgh, putting on shows in disused spaces and putting out short-run, home-made EPs. The collaborations forged then are still going now. The collaboration with Braindead Collective happened during a winter when I lived in Oxford, where we got together to improvise on a newly written song, recording the first take in a beautiful old church.

Has this year been typical in terms of being involved in so many different things? Could you tell us a bit about the Ghosts of Gone Birds project you’re involved in?

Things have been busier this year, for sure, taking on more projects. I like to keep busy. I’m not sure what is happening with Ghosts at the moment, as I think there’s been a personnel change recently. The last exhibition, in London, brought together a set of artists to make new work based on bird extinction in aid of the conservation charity BirdLife. I went with Ceri Levy (the organiser, up until recently), and a small group of artists to Malta in the spring, so we could all see the effects of illegal bird hunting first hand, and again base new work on this experience. I took hours of field recordings at dawn and dusk when hunting was most common, of gunshots punctuating the still air. We’re working on plans to use all of this work in some way next year.

You’re involved in a music project to commemorate the 400 year anniversary of the Pendle Witch Trials. Could you tell us a bit about that?

I grew up in a small village called Sabden on the side of Pendle Hill, in East Lancashire. 2012 is the 400th anniversary of the 1612 Pendle Witch Trials, a series of persecutions of people (mostly women) from the southern flank of Pendle Hill, on account of accusations of witchcraft. In the local area, the trials are now largely interpreted as cartoon-like caricatured black silhouettes of witches that adorn buses, pint glasses, gift shops and pubs. 2012 saw a host of local ‘celebrations’ of the trials, including a Guinness World Record attempt for the ‘number of people dressed as witches on a hill’.

Many of these celebrations and remembrances strike come across as a bit superficial and trite, I think, and so at the start of the year I set about trying to put together a record commemorating and interpreting the trials in a more appropriate way, however small. Early on, David Chatton Barker from Finders Keepers records offered his help, and to release the record through his imprint Folklore Tapes.

We’ve now finished the project, for release in November and have put together some great collaborators: Dean McPhee, David A Jaycock, drcarlsonalbion (Dylan Carlson from Earth), David Orphan, Tom Western, N Racker, Magpahi and others. Our contribution is a track called ‘The Mandrake’, a reinterpretation of a poem by Victorian author William Harrison Ainsworth, whose writings about Pendle and the trials echoed Walter Scott’s in the post-Clearance Highlands, lending an imagined romanticism to bleak histories. The project will be released on limited edition tape and download in a box containing writing on the trials, screen-printed maps, pressed nettles and other ephemera related to the area.

I’ve not been to the area, but there are some descriptive passages of the landscape in Robert Neill’s book Mist Over Pendle that are genuinely unsettling and imply a kind of menace in the landscape itself. Is there a case for arguing that certain areas/places can have a negative effect?

How do you mean ‘negative’ – on your own self, whilst you potter through the landscape?

I think that’s what I mean, yes – I think anyone who spends enough time out and about eventually has an inexplicable experience where an area/place/time just feels wrong somehow. I tend to be fairly sceptical about stuff like that and yet… Chris Watson said something in an interview in The Wire that’s always stuck with me (extract taken from issue 318)

I hadn’t seen that interview, nor had I heard of TC Lethbridge. It’s interesting. David Toop says something in Sinister Resonance about the role of sound in darkness as a conduit for haunting. About how ghosts prosper in the dislocation of the dark, as sound is an ephemeral, fragile, unreliable, perhaps even unfamiliar, means of understanding your surroundings. You hear differently when you record in the field. With your focus on sound, your concentration picks up on what you may otherwise miss in a more multi-sensory landscape (and soundscape). On Weald, we used a set of field recordings by ace sound artist Patrick Farmer. One recording, of tree roots rubbing underwater in a stream, stood out and serendipitously mirrored the rise and fall of the bellows of my harmonium grumbling and groaning at the start of ‘Stainforth Force’. I guess, when you dislocate sounds from their landscape, they lose their certainty of origin, and can be reinterpreted, in whatever way you choose. The drones in Richard Skelton’s recordings – recorded outside, a melding of the sound of the landscape and the instruments – are beautiful and very affecting for this reason. But as in the Chris Watson thing, this dislocated stream of sound can be really disorientating and troubling.

So, to return to the question, no, I don’t think that some landscapes are necessarily more menacing or ‘evil’ than others, it depends entirely on what sets of thoughts, ideas, preconceptions and experiences we bring to them. Some are more inherently dangerous, sure, some more bleak in landscape and weather. But never any inherent malevolent force. Going back to the idea of sound as a carrier of hauntings, I suppose it is in these dark, northerly landscapes- from Scotland, Scandinavia – that a rich set of mythology and folklore has sprung from.

But I think that your experience of a landscape is determined largely by what you bring to it, by the thoughts and knowledge you have in your head. It’s like the ‘peradam’ mountain in that novel Mount Analogue by Rene Daumal, some things are only found by those who – however unconsciously – go looking for them. I’ve no real love for the idea of ‘wilderness’, of a landscape where you can purge yourself of problems, get back to some simpler, Edenic nature. Every patch of the earth has been trampled, gridded and girdled by maps, development, history. Most people assemble different histories of a place, that go with what they’re comfortable with, what they have been told.

The set of writing about the Pendle Witches, by Robert Neill, William Harrison Ainsworth, even back to Thomas Potts’ original document of the trials might set a precedent for how a visitor might feel when walking on Pendle. But is Pendle more mysterious or spooky than another Pennine hill? No, but you’re guided by the preconceptions you bring. The narratives of the trials in the local area really are so mixed up. They veer from the misguided and disrespectful (I’ve a walking book by Ciccerone on the area, that punctuates walks with descriptions of the accused witches as ‘repulsive old hags’ and ‘ decrepit, sightless, old crones’) to the banal and cartoon-like (cuddly toy witches, mass walks up Pendle dressed in capes and pointy hats). People tend to forget that these were real people, caught up in a web of persecution, superstition and fear.

The ‘Pendle 1612’ release that I’ve part-curated is a response to this. The box in which the release is housed will contain a series of ephemera and information, including a map of the area, and the witches route to trial from Pendle to Lancaster. We’ve spent a lot of time populating this map with photographs, grids, information that we think is relevant to the trials, which has been an interesting process that I guess ties together a lot of what I’ve talked about here, especially when trying to highlight the role of the persecutors in the trials. What to you include, prioritise and draw links between, when trying to construct a visual history?

In the middle of this process, I went to the Patrick Keiller Robinson exhibition at Tate Britain in London. I like Keiller a lot, especially his Robinson stuff. It seems a rich, almost playful approach to these knotty problems – the way he assembles such a constellation of – at times seemingly ephemeral – information, and traces a line made by walking through it all. To me, his work is encouragement to delve into the history of places and landscapes important to you, that through putting all this information that others have perhaps disregarded together, the most important thing is that you become connected to these places and landscapes in your own individual way. In a way, that’s what Weald was. I have no historical connection with Lancashire other than I was born here – my family are from Ireland and Derbyshire. It was a way of finding meaning.